Earlier this year, a childhood friend of mine lost her 11 month old baby girl to cancer. Of course, her death left dozens, if not hundreds of people in the community heartbroken and in disbelief. She had been treated at one of the best hospitals in the nation, if not the world. The doctors used the latest technology and drugs to monitor and fight the cancer, yet they were ultimately unsuccessful. The death of a baby in today's era of modern medicine is rare and I think that is one of the reasons why it affects us so deeply. But we forget that not long ago, when childbirth was rough, when there were no vaccinations or antibiotics, when nutrition was poor, and when living conditions were not as sanitary as they are today, the death of an infant was much more common. In 1901, the infant mortality rate in the U.S. was about 136 deaths out of 1,000 live births. (And THAT number was an improvement over the 200 - 300 rates per 1,000 estimated in the 19th century and earlier.) By contrast, in 2010 the infant mortality rate in the U.S. was approximately 6.8 deaths per 1,000 live births.

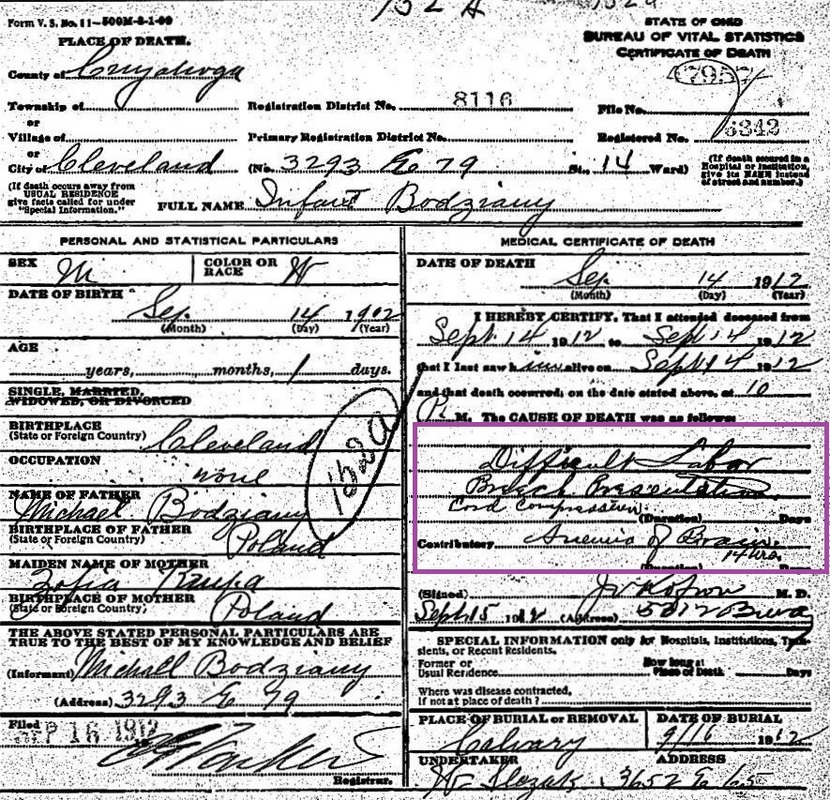

I came across a couple of newborn death certificates fairly early in my research into my own relatives. I was searching historical documents online for the names of my great-grandparents, Michael and Sofia Bodziony. (At this point, I didn't know my great-grandmother's maiden name - these death certificates gave me the answer. It was kind of a "Eureka!/sigh of sadness" moment, if that makes sense.)

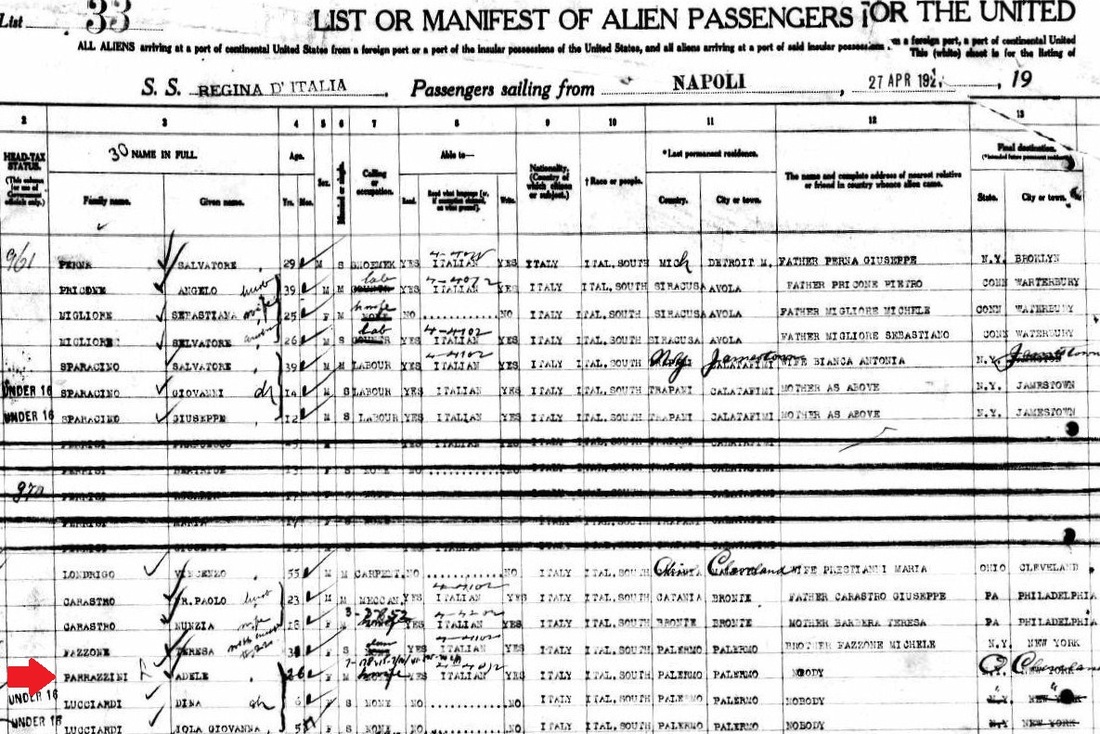

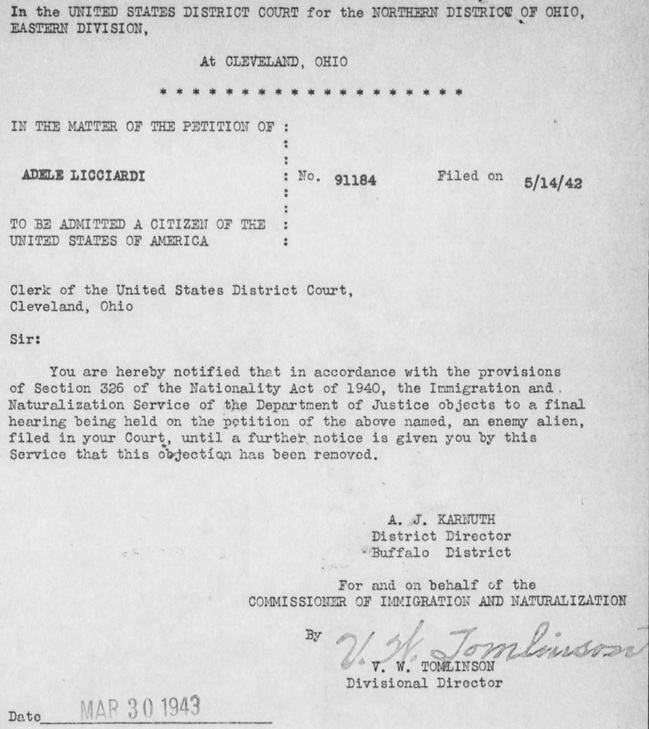

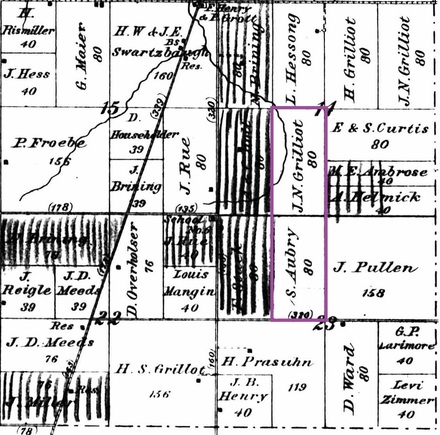

As I started researching Tony's side of the family, I found similar patterns all too often. In the 19th century (and earlier), death certificates weren't routinely issued, so a gravestone may be the only proof of where and when a death occurred (and may be the only evidence that a person existed at all!) Even if I can't find an actual record of an infant death, such as a death record or gravestone, it can be inferred by spacing of other children in the family. The natural spacing of children for a couple with average fertility is about 18 months - 2 years. So, if I see in a census schedule that the children are ages 2, 4, 8, 10, 11, then it's probably a good bet that the couple either suffered a late miscarriage or that a young child, who would have been about 6 yrs at the time of census, died. However, I may never figure out the name or birthdate of that child.

Coming across records like these make me grateful to live in 2012, grateful to be blessed with the resources and knowledge to keep my children safe and healthy. And just because the death of an infant was much more common in our ancestors' times, it doesn't mean that their families suffered from it any less than we do today. Just like today, I'm sure a mother back then would have carried her grief of a lost child in her heart and mind until the day she died.

©2014, copyright Emily Kowalski Schroeder