|

I never really got to know my paternal grandmother; she passed away when I was only four years old. This was one of her tins. It's nothing fancy - just a painted Decoware tin with a few small rust spots and dents in it. But, other than the photos and documents I have uncovered via my genealogy research, it's the only thing of hers that I have, so it's special to me. My aunt gave it to me a couple years ago filled with a batch of my grandma's original-recipe chocolate chip and walnut cookies. That's a photo of them below. The story goes, my dad and his three siblings would squabble over whose cookies had more chocolate chips in them, so my grandmother just started putting exactly five in every cookie.

3 Comments

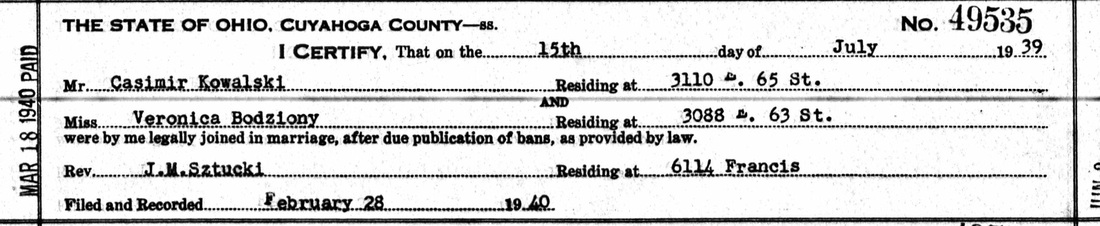

Wedding Day photo of my grandparents, Casimer Kowalski and Veronica Bodziony. The wedding took place on July 15, 1939 at Saint Hyacinth Church in Cleveland, Ohio. Their county marriage record is shown below (They misspelled my grandfather's first name.) Source Citation: Cuyahoga County Archive; Cleveland, Ohio; Cuyahoga County, Ohio, Marriage Records, 1810-1973; Volume: Vol 190; Page: 192; Year Range: 1895 Aug - 1941 Jun.

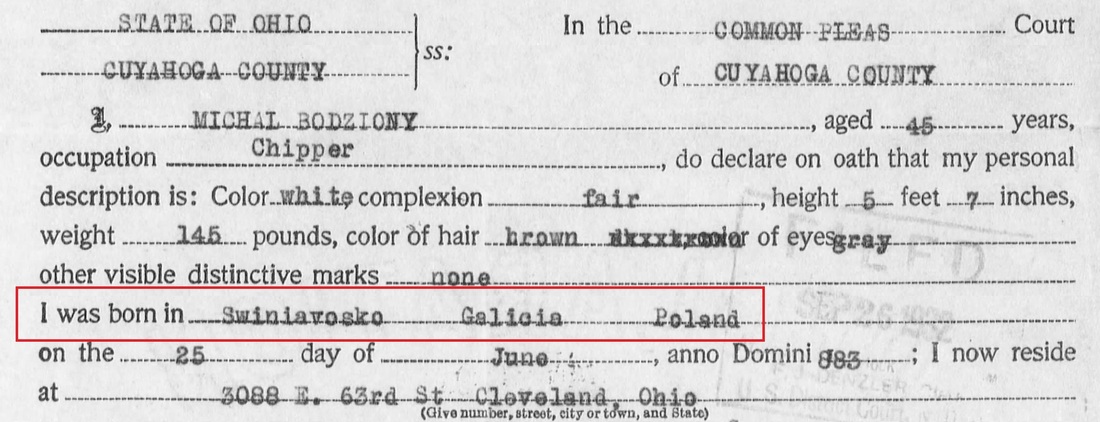

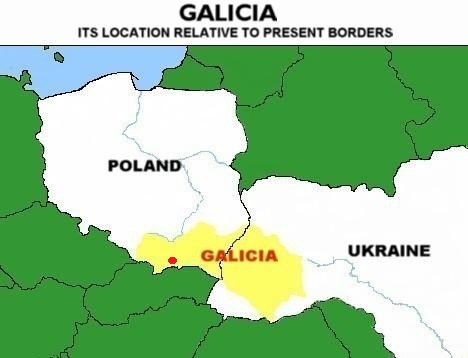

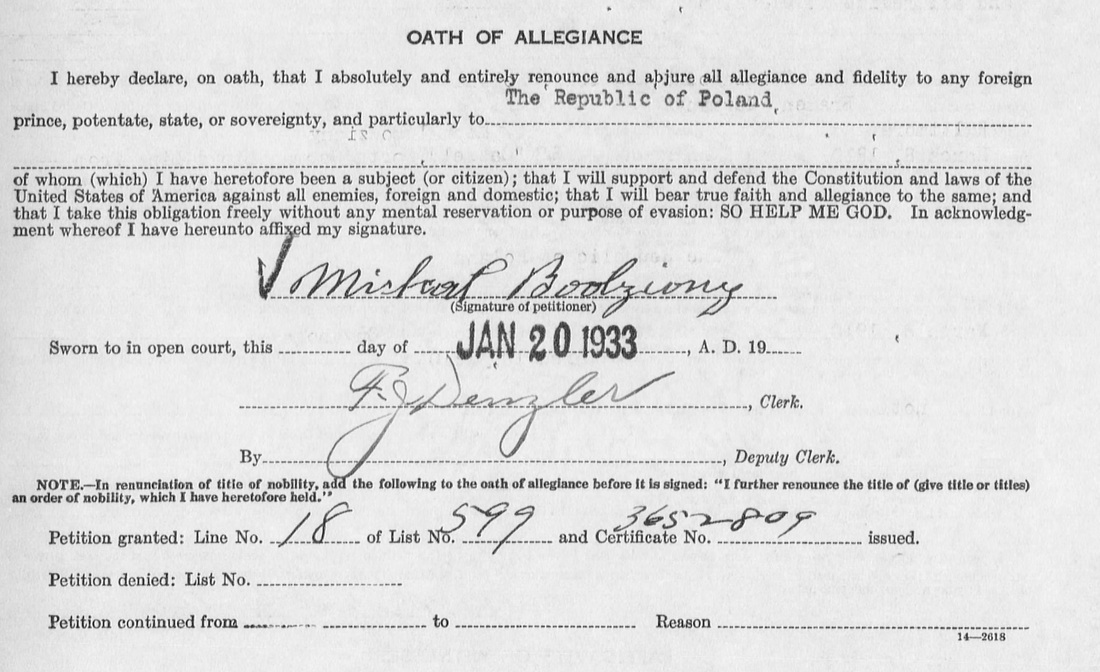

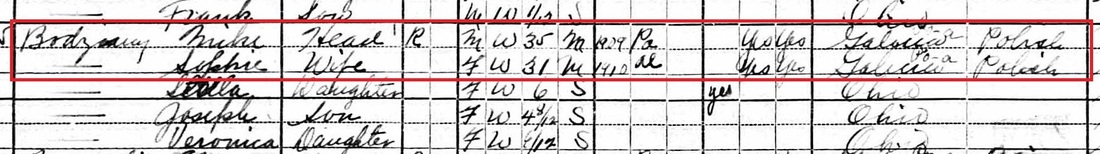

©2012, copyright Emily Kowalski Schroeder When you are studying your family's history, some of the most exciting documents you can come across in your research are immigration-related papers: Ship manifests and applications for citizenship. Not only do they tell you exactly where and when your ancestors entered the country, but they also contain important information about where your ancestor was from, which is absolutely vital if you want to start researching family lines in other countries. I was excited when I found these sorts of documents belonging to my great-grandfather, Michael Bodziony. I had already known that he was ethnically Polish, obviously spoke Polish and settled in a very Polish community in Cleveland. However, nobody in the family knew where exactly he was from. I found his name on a 1910 ship manifest and looked across the sheet from his name to the three columns that read, "Nationality (country of which citizen or subject), Race of People, Country (of last residence.)" And in these columns is listed, "Austria, Polish, Austria." Ok, now I'm not an expert in 19th central European history, but I vaguely remember learning in history class about the extent and longevity of the Austrian Empire, so I am not surprised. I then was able to find Michael's citizenship papers. Here is his 1929 Declaration of Intention: I also found a reference to Galicia as Michael and Sophie Bodziony's place of birth in the 1920 U.S. Census:  Source Citation: Year: 1920; Census Place: Cleveland Ward 14, Cuyahoga, Ohio; Roll: T625_1366; Page: 15A; Enumeration District: 272; Image: 37. Source Information: Ancestry.com. 1920 United States Federal Census [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2010. Images reproduced by FamilySearch. I do NOT remember learning anything about Galicia at any point in my schooling, so I was curious. Wikipedia to the rescue! The Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria was part of Austria-Hungary from 1772-1918, so my great-grandfather WAS technically born in Galicia, Austria and it WAS still part of Austria when he immigrated to America in 1910. (By the way, the name of his birthplace was spelled incorrectly - it should have read, 'Swiniarsko.') Here are Galicia's borders overlayed on a modern map of the region, and that red dot is the location of Michael's hometown. (Map from http://www.germangenealogist.com/2011/06/03/3331/) Now, by the time Michael took his Oath of Allegiance to the U.S. in 1933, the area in which his birthplace was located had become part of the sovereign nation known as 'The Republic of Poland', which you can see on this form: I enjoyed solving this little mystery for myself, probably because it involved looking at maps, which I love to do. Trying to understand the history behind all these name and border changes was a little more difficult, but I would like to someday read a (good) history of Poland. And I intend to write more blog posts in the future about how historical events in Europe may have influenced my and my husband's ancestors to make the decision to immigrate to America.

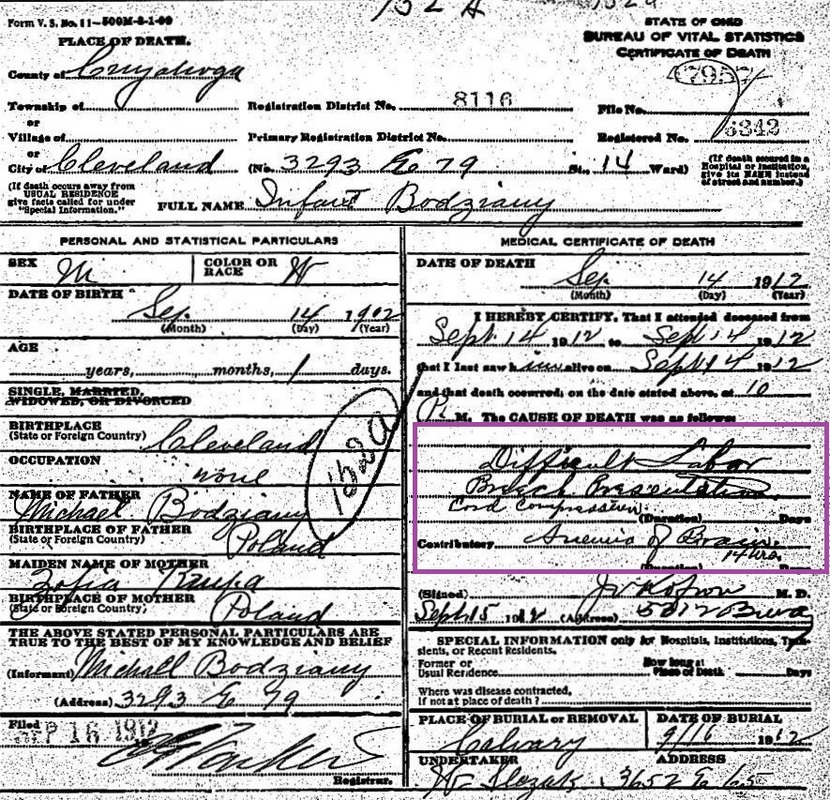

©2012, copyright Emily Kowalski Schroeder If you've ever done genealogy research, you probably already know that one of the most emotionally heart-breaking records to come across is a baby's death certificate. Even though it is not your child, even though you never knew the child or his parents or his grandparents, it still leaves you sad. Earlier this year, a childhood friend of mine lost her 11 month old baby girl to cancer. Of course, her death left dozens, if not hundreds of people in the community heartbroken and in disbelief. She had been treated at one of the best hospitals in the nation, if not the world. The doctors used the latest technology and drugs to monitor and fight the cancer, yet they were ultimately unsuccessful. The death of a baby in today's era of modern medicine is rare and I think that is one of the reasons why it affects us so deeply. But we forget that not long ago, when childbirth was rough, when there were no vaccinations or antibiotics, when nutrition was poor, and when living conditions were not as sanitary as they are today, the death of an infant was much more common. In 1901, the infant mortality rate in the U.S. was about 136 deaths out of 1,000 live births. (And THAT number was an improvement over the 200 - 300 rates per 1,000 estimated in the 19th century and earlier.) By contrast, in 2010 the infant mortality rate in the U.S. was approximately 6.8 deaths per 1,000 live births. I came across a couple of newborn death certificates fairly early in my research into my own relatives. I was searching historical documents online for the names of my great-grandparents, Michael and Sofia Bodziony. (At this point, I didn't know my great-grandmother's maiden name - these death certificates gave me the answer. It was kind of a "Eureka!/sigh of sadness" moment, if that makes sense.) Michael and Sofia had been married less than a year and this was their first child. The cause of death is listed as 'anemia of brain' with difficult labor, breech presentation and cord compression. These are the days before prenatal care and obstetricians. Most women only had a local midwife to assist in births, and, in the days before c-sections, if things went wrong there was not much the local doctor could do for the mother or the infant. After two successful pregnancies and births, Sofia had another difficult labor which resulted in a stillborn baby boy. (She went on to have three more daughters who lived into adulthood.)

As I started researching Tony's side of the family, I found similar patterns all too often. In the 19th century (and earlier), death certificates weren't routinely issued, so a gravestone may be the only proof of where and when a death occurred (and may be the only evidence that a person existed at all!) Even if I can't find an actual record of an infant death, such as a death record or gravestone, it can be inferred by spacing of other children in the family. The natural spacing of children for a couple with average fertility is about 18 months - 2 years. So, if I see in a census schedule that the children are ages 2, 4, 8, 10, 11, then it's probably a good bet that the couple either suffered a late miscarriage or that a young child, who would have been about 6 yrs at the time of census, died. However, I may never figure out the name or birthdate of that child. Coming across records like these make me grateful to live in 2012, grateful to be blessed with the resources and knowledge to keep my children safe and healthy. And just because the death of an infant was much more common in our ancestors' times, it doesn't mean that their families suffered from it any less than we do today. Just like today, I'm sure a mother back then would have carried her grief of a lost child in her heart and mind until the day she died. ©2014, copyright Emily Kowalski Schroeder |

Emily Kowalski SchroederArchives

April 2017

Categories

All

|

| The Spiraling Chains: Kowalski - Bellan Family Trees |

|